We Need Public Power for Energy Equity

by isaac sevier · Sep 11, 2023 14:46 · 9 minute read

We have to expand public ownership of the electricity system rapidly and comprehensively. With more than one-quarter of all U.S. households currently experiencing deep energy insecurity, the requirement of private utilities to produce competitive profits for their investments is fundamentally opposed to the equally urgent tasks of resisting energy apartheid and greening our buildings and the power sector.

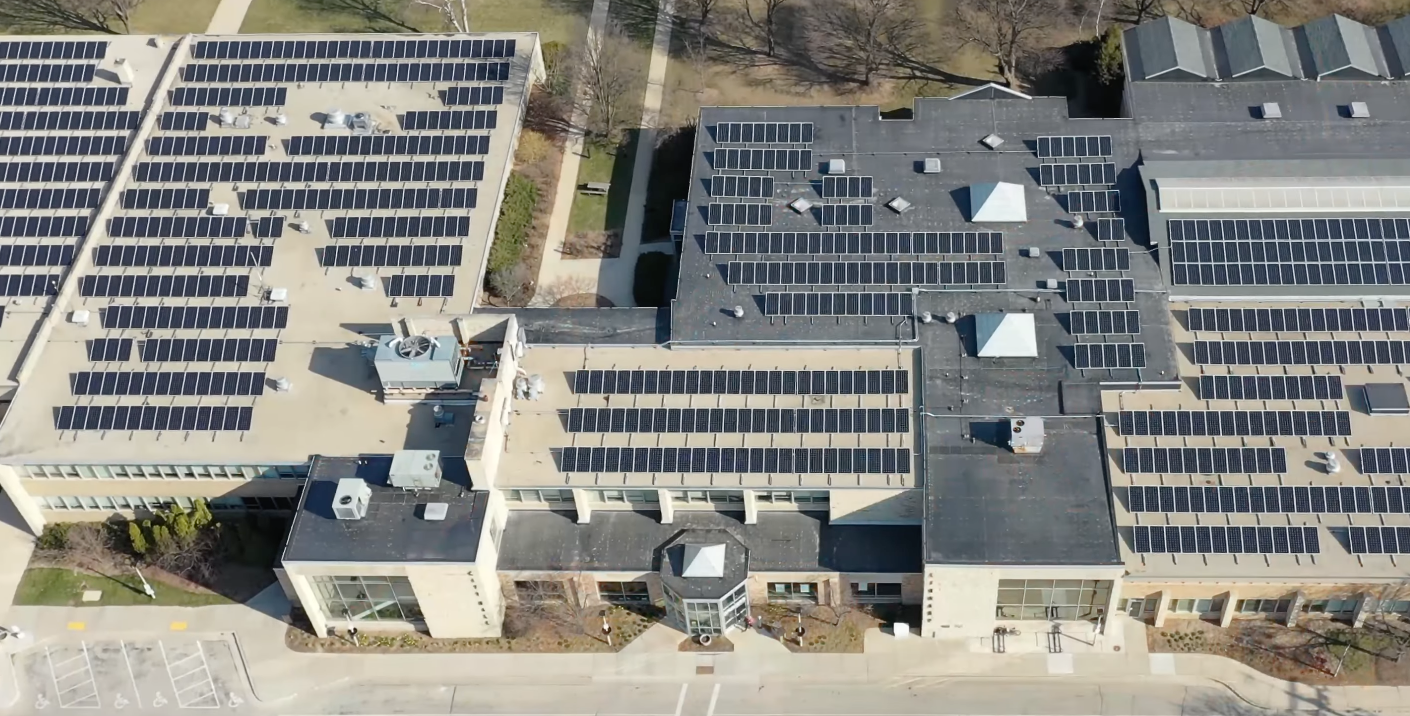

Photo by Arch Solar from YouTube

If we want to create an equitable future for electricity in the United States, we have to expand public ownership of the electricity system rapidly and comprehensively. With more than one-quarter of all U.S. households currently experiencing deep energy insecurity, private ownership of generation and the grid and the requirement of private utilities to produce competitive profits for their investments is not only insufficient for the tasks ahead under any rapid decarbonization scenario, it is fundamentally opposed to the equally urgent tasks of resisting energy apartheid as we green the power sector.

The American Public Power Association declares that public power is “driven by the mission to support the people [emphasis mine] who rely on the public electricity system” and to support the communities the utility exists in more generally through the electric service they provide, through revenues that enter local government budgets, and through being a positive force for good more generally by being a good community actor. Johanna Bozuwa, of the Climate and Community Project, and her co-authors on “The Power of Community Utilities” proposes that we can and should envision the public electric utility as a “community anchor” much like hospitals or universities, the “eds and meds” rooted in place that serve as an integral part of the community’s long term health.

Playing this role is a natural fit for a publicly-owned utility, unlike the for-profit, privately owned utility model, which has a significant fiduciary obligation to extract wealth from the community and send it to shareholders. As a recent example, for-profit utility company Appalachian Power Company, a subsidiary of American Electric Power, sought and won a guaranteed rate of return of nearly 10% in a recent settlement, essentially bagging an additional $127 million in revenues on top of existing revenue of $1.5 billion… all for their shareholders’ benefit. That’s money that public utilities don’t have to grab from their customers and stays in people’s pockets or can be sent directly back to local communities instead.

To be sure, the public utility model, like every part of our democracy, needs continuous care and cultivation to ensure it stays healthy and thrives over the long term. Like all corporations, public corporations need watchdogs and transparency requirements in order to be accountable to the communities they serve. Being publicly owned doesn’t make utilities automatically superior as a definitional matter. But being publicly owned gives us all an opportunity to exercise our democratic rights, which i think is worth fighting for now more than ever as control over our future seems more and more at risk due to gerrymandering, a deeply corrupted Supreme Court, and the current power of global corporations and billionaires to shape our world.

I was asked to speak with a group of organizers in the Midwest about “what equity means for public power”. As i thought more about it, i realized that what i really wanted to talk about was what public power means for equity, the reverse of the topic’s framing.

Here’s why: in the United States, we treat access to electricity as an individualized burden, and the summary data shows it. Energy insecurity plagues more than 33 million households in the U.S. (one quarter of all households). In electricity policy circles, this economic inequality is so well-known and long-standing that it is referred to colloquially as the “heat or eat” dilemma, meaning the choice people face between using their limited budgets to pay for either electricity, food, or medicine. This is the environment in which we must pursue deep decarbonization of the grid, our homes and all of the rest of our buildings, and every mode of transportation that currently uses fossil fuels.

It has long been accepted wisdom in the climate movement that as global, collective action on fossil fuel emissions is delayed, the actions required to keep global warming limited to 1.5°C will need to become more significant over shorter time periods. In other words, earlier actions could be smaller and add up over time, while later actions - if delayed - would need to be larger and less incremental the longer we wait. We are now in the latter scenario, with the attendant equity dilemma of persistent, structural poverty.

As we think about solutions, we also have to organize and strategize from the reality outside the electricity sector, too. The “heat or eat” dilemma is being exacerbated by the fact that food prices rose by 10% last year. The USDA projects they will rise another 6% this year and keep rising next year, too. Energy insecurity is not only being impacted by the actions inside the energy sector, it is being impacted by the rising inequality present across the economy.

There is good news. The price of nearly all configurations of renewables - including pairings with energy storage - is now at cost-parity to conventional fossil electricity generation, according to this year’s updated levelized cost of energy analysis from Lazard. It’s also at cost-parity in many cases with the marginal costs of existing conventional electricity generators, meaning building new renewables to generate additional electricity has the same costs as running existing plants at higher capacity factors. This means that under existing and commonly accepted utility planning principles, business fundamentals for providing electricity and battery storage are now on the side of renewables, for for-profit and not-for-profit utilities alike.

However, cost is not what is will drive the rest of the green transition to renewables. Profit is. Brett Christophers, in a study of renewables’ price competitiveness with fossil fuels, points out that internal rate of return scenarios possible for renewable power projects are limited to between four and eight percent, much lower than the 15% and greater that can be achieved developing oil and gas projects. This means that, for a corporation choosing between spending capital on renewables projects or fossil fuel projects, if maximizing for returns alone, will likely not choose to develop the renewables projects. Now that renewables have broadly achieved cost-parity with fossil fuel-based electricity technology, we should critically examine the investment logic that will drive future decisions of the private corporation and financial communities.

More discussion of the limits of private finance by Advait Arun, a former analyst at the U.S. Treasury, names this as the “hurdle rate” problem within the private finance community more widely. Applied to this question of utility-scale investments in renewables, Arun’s analysis would suggest fiduciary commitments to shareholders will prevent investments in renewables by most large fund managers, who are not comparing only the returns of renewables projects against fossil fuel projects but the returns of renewables projects to a much wider basket of possible investments across the economy. Market failures this month in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico offshore wind auction and the UK wind auction, as well as the downgrade of credit rating for Ørsted, suggest we may beginning to see more data points trailing Christophers’s analysis from 2021 materializing in front of us.

This means that not-for-profit, public utilities have a critical and, in my opinion, irreplaceable role to play in creating energy equity. A role that cannot be filled by for-profit, private utility corporations. That role is to keep building renewables, bring down the costs of electricity, and take significant action to eliminate energy insecurity through democratic mandates to prioritize a blend of outcomes - not to chase returns.

Earlier this year, the American Public Power Association reported that less than 2% of all utility-scale electricity generation projects under construction, permitted, pending application, or proposed will be built by public power authorities. This suggests that both capital availability and expertise in developing power generation facilities have been extremely low. But with the direct pay tools provided to municipal and not-for-profit entities under the Inflation Reduction Act, public utilities can begin to develop the expertise needed. Free of the hurdle rate logic that will dictate private utility and private finance decision making, public utilities can take advantage of the cost-parity regime we are in where private utilities will turn away, and begin to take a significant share of the ownership of renewables going forward. Public utilities can also be mandated through democratic governance to optimize for multiple outcomes, like equity, affordability, and emissions reductions, on top of pursuing low portfolio-wide costs of electricity generation. This could include innovating their business models to eliminate the costs of electricity for the poorest customers they serve, eliminating energy insecurity within their territories.

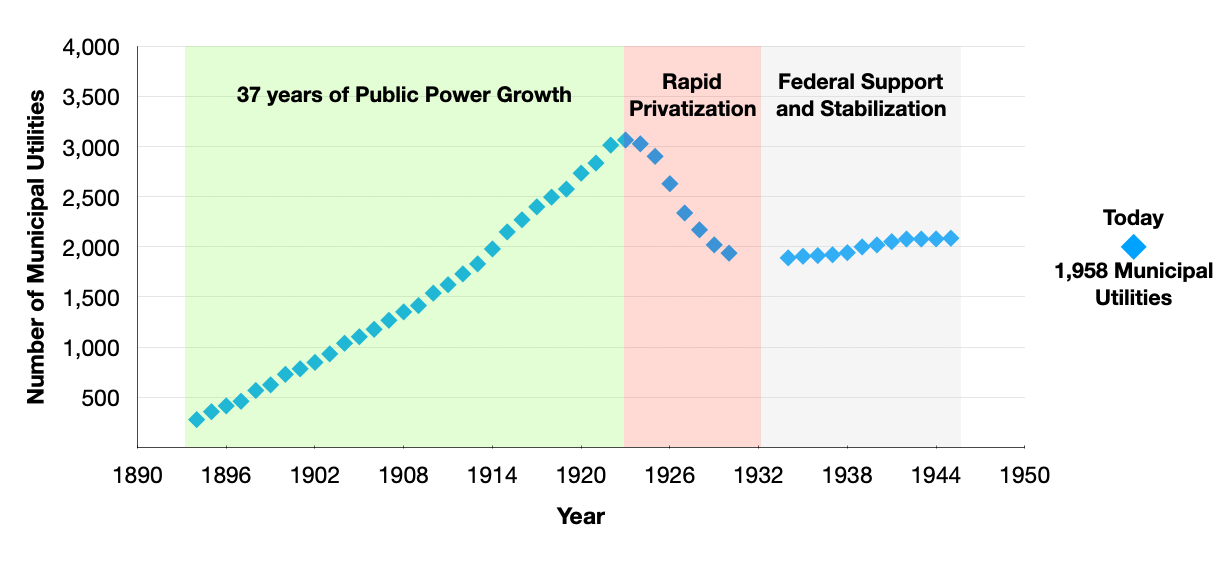

If this feels too fantastic to be possible, we can look to a historic analog to ask what could be possible. From a small book about municipal utilities by David Schap, I pulled two short data series together which show the rise of municipal utilities, a period of rapid privatization, and the subsequent stabilization due to federal support and investment made possible during the New Deal era, specifically 1932-33. In addition to literally stopping the collapse of the publicly owned utility sector, the injection of investment helped public utilities to bring down the costs of electricity significantly, resulting in a period of growth for public utilities after nearly a decade of freefall. Schap mentions that the attractiveness of public - and therefore, democratic - ownership as well as lower rates began to build significant political support for expansion of existing public utility territories, even bringing otherwise unwilling private utilities to the table to negotiate sales back to municipalities on more favorable terms to the public.

Chart of Number of Municipal Utilities over Time from 1894-1945

The unique conditions we are experiencing are well suited for the leadership of public institutions. Only public institutions, free of the requirements to make an energy transition profitable, can rise to the combined challenges of deep, long-standing racial and economic equity, rapid grid transformation, and steep emissions reductions. The Inflation Reduction Act’s direct pay provisions have the potential to be the largest injection of support for the growth and leadership of our public utilities in the last century. It is up to the public utility managers themselves, along with deep, sustained support from the communities they ostensibly serve, to find the courage to lead and the ambition to act. Doing so has the potential to cement public utilities as one of the most prized anchor institutions in any community, if done well with equity at the center.